State of function decompilation in Javascript

It’s always fun to see something described as “magic” in Javascript world.

One such example I came across recently was AngularJS dependency injection mechanism. I’ve never been familiar with the concept, but seeing it in practice looked clever and convenient. Not very magical though.

What is it about? In short: defining required “modules” via function parameters. Like so:

Notice the $scope, $timeout, $http identifiers.

Aha. So instead of passing them as strings or vars or whatever, they’re defined as part of the source. And of course to “read” the source there could only be one thing involved…

The kind that we used in Prototype.js to implement $super back in 2007? Yep, that one. Later making its way to Resig’s simple inheritance (used in a safe fashion) and other places.

Seeing a modern framework like Angular use function decompilation got me surprised. Even though it wasn’t something Angular relied on exclusively, this black magic has been somewhat frowned upon for years. I wrote about some of the problems associated with it back in 2009.

Something so inherently non-standard and so varying among implementations could only be compared to user agent sniffing.

But is it, really? Could it be that things are not nearly as bad these days? I last investigated this 4 years ago — a significant chunk of time. Could it be that implementations came to some kind of unification, when it comes to function string representation? Am I completely outdated?

Curious, I decided to take a look at the current state of affairs. Could function decompilation be relied on right now? What exactly could we rely on?

But first..

Theory

To put simply, function decompilation is the process of accessing function code as a string (then parsing its body or extracting arguments or whatever).

In Javascript, this is done via toString() of function objects, so fn.toString() or String(fn) or fn + '' or anything else that delegates to Function.prototype.toString.

The reason this is deemed unreliable in Javascript is due to its non-standard nature. A famous quote from ES5 spec states:

15.3.4.2 Function.prototype.toString( )

An implementation-dependent representation of the function is returned. This representation has the syntax of a FunctionDeclaration. Note in particular that the use and placement of white space, line terminators, and semicolons within the representation String is implementation-dependent.

Of course when something is implementation-dependant, it’s bound to deviate in all kinds of ways imaginable.

Practice

..and it does. You would think that a function like this:

.. would be serialized to a string like this:

And it almost does. Except when some engines omit newlines. And others omit comments. And others omit “dead code”. And others include comments around (!) function. And others hide source completely…

Back in the days, things were really bad. Safari <=2.x, for example, didn’t even conform to valid Function Declaration syntax. It would go wild with things like “(Internal Function)” or “[function]” or drop identifiers from NFE’s, just because.

Back in the days, some of the mobile browsers (Blackberry, Opera Turbo) hid the code completely (replacing it with polite “** /* source code not available */ **” comment instead or similar), supposedly to “save” on memory. A fair optimization.

Modern days

But what about today? Surely, things must have gotten better. There’s a convergence of engines, domination of relatively sane WebKit, lots of standardization, and tremendous increase in engines performance.

And indeed, things are looking good. But it’s not nearly all nice and peachy yet, and there’s more “fun” on the horizon.

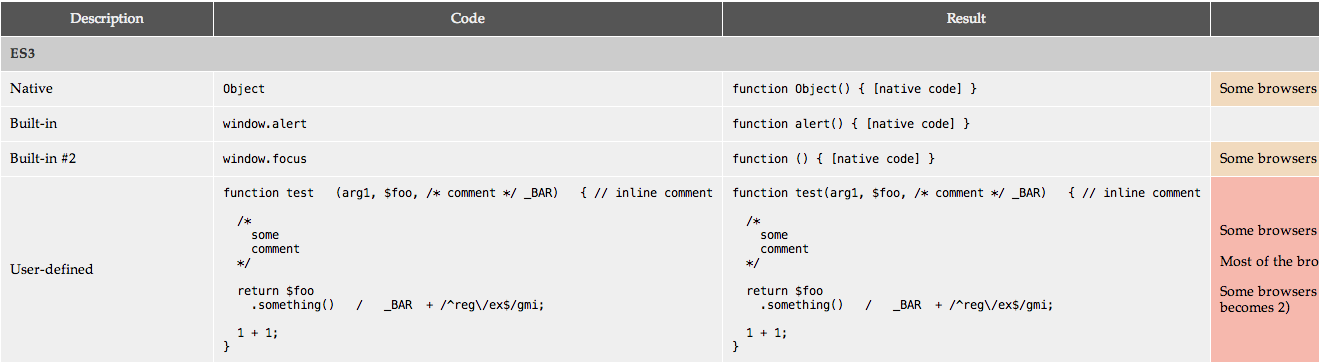

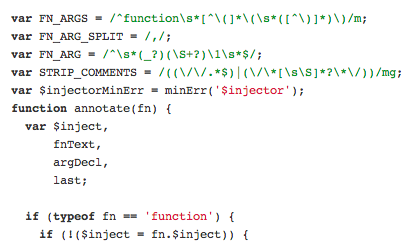

I made a simple test page, checking various cases of functions and their string representations. Then tested it on desktop browsers, including pretty “old” ones (IE6+, FF3+, Safari4+, Opera 9.6+, Chrome), as well as slew of mobiles and looked at common patterns.

Decompilation purpose

It’s important to understand different purposes of function decompilation in Javascript.

Serializing native, built-in functions is different from serializing user-defined ones. In case of Angular, for example, we’re talking about user-defined function, so we don’t have to concern ourselves with the way native functions are serialized. Moreover, if we’re talking about retrieving arguments only, there’s definitely less deviations to deal with; unlike if we wanted to “parse” the source code.

Some things are more reliable; others — less so.

User-defined functions

When it comes to user-defined functions, things are pretty uniform.

Aside from oddball and dying environments like IE<9 — which sometimes includes comments (and even parens) around functions in their string representation — or Konqueror, that omits function body brackets from new Function -generated functions.

Most of the deviations are in whitespace (and newlines). Some browsers (e.g. Firefox <17) strip all comments from source code, and remove “dead”, unreachable code.

But don’t get too excited as we’ll talk about what future holds in just a bit…

Function constructor

Things are also a bit hectic in generated functions (using new Function(...)) but not much. While most of the engines create function with “anonymous” identifier, the spacing and newlines are inconsistent. Chrome also inserts extra comment after parameters list (extra comment never hurts, right?).

becomes:

Bound functions

Every single supporting engine that I’ve tested represents bound (via Function.prototype.bind) functions the same way as native functions. Yes, that means bound functions “lose” their source from string representation.

Arguably this is a reasonable thing to do; although a bit of a “wat?” when you first see it — why not use “[bound code]” instead?

Curiously, some engines (e.g. latest WebKit) preserve function’s original identifier and some don’t.

Non-standard

What about non-standard extensions? Like Mozilla’s expression closures.

Yep, those are still represented as they’re written; without function body brackets (technically, a violation of Function Declaration syntax, which MDN page on Function.prototype.toString doesn’t even mention; something to fix!).

ES6 additions

I was almost done writing a test case, when a sudden thought crossed my mind. Hold on a second… What about EcmaScript 6?!

All those new additions to the language; new syntax that changes the way functions look — classes, generators, rest params, default params, arrow functions. Won’t they affect function representation as well?

Quick test shed the light — they do. Of course. Firefox 24+, leading ES6 brigade, reveals string representation of these new constructs:

Examining ES6 spec confirms this further:

An implementation-dependent String source code representation of the this object is returned. This representation has the syntax of a FunctionDeclaration, FunctionExpression, GeneratorDeclaration, GeneratorExpession, ClassDeclaration, ClassExpression, ArrowFunction, MethodDefinition, or GeneratorMethod depending upon the actual characteristics of the object. In particular that the use and placement of white space, line terminators, and semicolons within the representation String is implementation-dependent.

If the object was defined using ECMAScript code and the returned string representation is in the form of a FunctionDeclaration FunctionExpression, GeneratorDeclaration, GeneratorExpession, ClassDeclaration, ClassExpression, or ArrowFunction then the representation must be such that if the string is evaluated, using eval in a lexical context that is equivalent to the lexical context used to create the original object, it will result in a new functionally equivalent object. The returned source code must not mention freely any variables that were not mentioned freely by the original function’s source code, even if these “extra” names were originally in scope. If the source code string does meet these criteria then it must be a string for which eval will throw a SyntaxError exception.

Notice how ES6 still leaves function representation implementation-dependent although clarifying that it no longer conforms to just FunctionDeclaration syntax. Also notice an interesting additional requirement — “returned source code must not mention freely any variables that were not mentioned freely by the original function’s source code” (bonus points if you understood this in less than 7 tries).

I’m unclear on how this will affect future engines and their representation. But one thing is certain. With the rise of ES6, function representation is no longer just an optional identifier followed by parameters and function body. There’s a whole lot of new stuff coming.

Regexes will, once again, have to be updated to account for all the changes (did I say it’s similar to UA sniffing? hint, hint).

Minifiers & Preprocessors

I should also mention couple of old chestnuts that never quite sit well with function decompilation — minifiers and preprocessors.

Minifiers like UglifyJS, and preprocessors/compilers like Caja tend to tweak the hell out of source code and rename parameters. This is why Angular’s dependency injection doesn’t work with minifiers unless alternative methods are used.

Perhaps not a big deal, but still a relevant issue and definitely something to keep in mind.

TL;DR & Conclusions

To sum things up: it appears that function decompilation is becoming safer but — depending on your parsing needs — it might still be unwise to rely exclusively on.

Thinking to use it in your app/library?

Remember that:

- It’s still not standard

- User-defined functions are generally looking sane

- There are oddball engines (especially when it comes to source code placement, whitespaces, comments, dead code)

- There might be future oddball engines (particularly mobile or unusual devices with conservative memory/power consumption)

- Bound functions don’t show their original source (but do preserve identifier… sometimes)

- You could run into non-standard extensions (like Mozilla’s expression closures)

WinterES6 is coming, and functions can now look very different than they used to- Minifiers/preprocessors are not your friend

P.S. Functions with overwritten toString methods and/or Proxy.createFunction are a different kind of beast; we can consider those a special case that would require a special consideration.

Special thanks to Andrea Giammarchi for providing some of the mobile tests (not available on BrowserStack).

Did you like this? Donations are welcome

comments powered by Disqus