Refactoring single page app

A tale of reducing complexity and exploring client-side MVC

Skip straight to TL;DR.

Kitchensink is your usual behemoth app.

I created it couple years ago to showcase everything that Fabric.js — a full-blown <canvas> library — is capable of. We’ve already had some demos, illustrating this and that functionality, but kitchensink was meant to be kind of a general sandbox.

You could quickly try things out — add simple shapes or images or SVG’s or text; move them around, scale, rotate, delete, group, change colors, opacity; experiment with locking or z-index properties; serialize canvas into image or JSON or SVG; and so on.

And so there was a good old, single kitchensink.js file (accompanied by kitchensink.html and kitchensink.css) — just a bunch of procedural commands and conditions, really. Pressed that button? Add a rectangle to the canvas. Pressed another one? Load an image. Was object selected on canvas? Enable that button and update its text. You get the idea.

But things change, and over time the app grew and grew until the once-simple kitchensink.js became too big for its own good. I was starting to notice more and more repetition, problems with navigating and maintaining code. Those small weird glitches that live in the apps without authoritative data source; they came as well.

I was looking at a 1000+ LOC JS file, realizing it’s time to refactor.

But there was a bit of a pickle. You see, kitchensink is all about managing <canvas>, through Fabric, and frankly I had no idea how to best approach an app like this. If this was your usual “User” or “Collection” or “TodoItem” data coming from a server or elsewhere, I’d quickly throw together few Backbone.Model’s and call it a day. But with Fabric, we have an object model on top of <canvas>, so there’s just a collection of abstract visual objects and a way to operate on those objects.

Is it possible to shoehorn MVC onto all this? What exactly would become a model or the views? Is it even a good idea?

The following is my step-by-step refactoring path, including close look at some MVC-ish solutions. You can use it to get ideas on revamping your own spaghetti app, and/or to see how to approach design of <canvas>-based app, specifically. Each step is made as a separate commit in fabricjs.com repo on github.

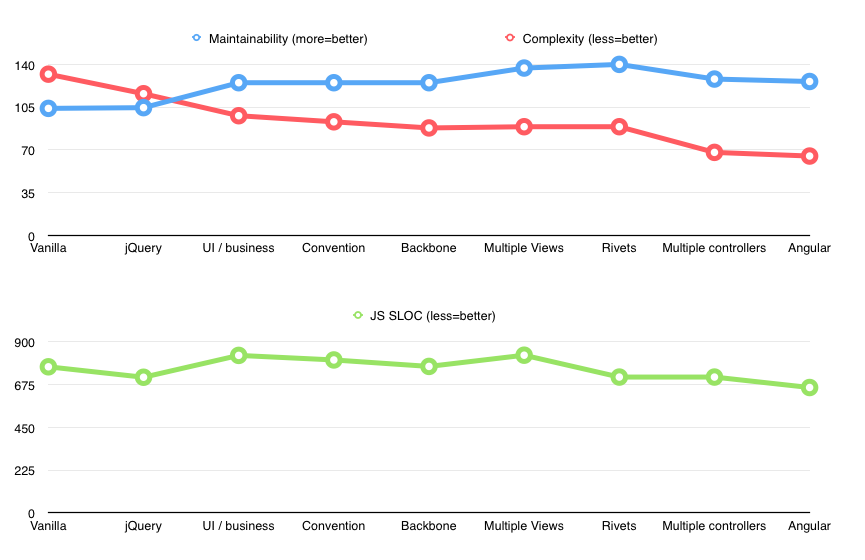

Complexity vs. Maintainability

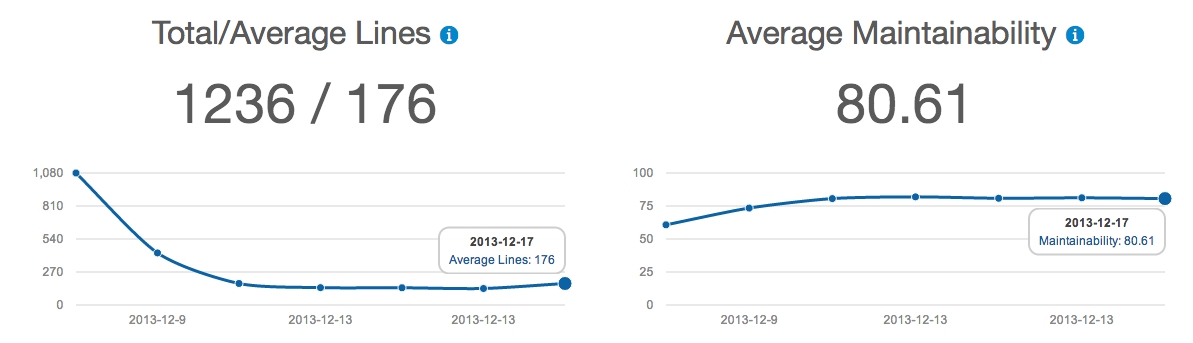

Before changing anything, I decided to do a little experiment and statically analyze complexity of an app. Not to tell me that it was in shitty state; that I already knew. I wanted to see how it changes based on different solutions.

There are few ways to analyze JS code at the moment. There’s complexity-report npm package, as well as jscomplexity.org (both rely on escomplex). There’s Plato that provides visual tracking of complexty (based on complexity-report). And there’s good old JSHint; it has its own cyclomatic complexity calculation.

I used complexity-report because it has more granular analysis and has this useful metric — “Maintainability”. What exactly is it and why should we care about it?

Here’s a simple example:

This chunk of code has cyclomatic complexity (CC) of 1. It’s just a single function call. No conditional operators, no loops. Yet, it’s pretty scary (actual code from Fabric.js, btw; shame on me).

Now look at this code:

It also has cyclomatic complexity of 1. But it’s clearly significantly easier to understand and maintain.

Maintainability, on the other hand, is reported as 151 for the first one and 159 for the second (the higher the better; 171 being the highest). It’s still not a big difference but it’s definitely more representative of overall state of the code, unlike cyclomatic complexity.

complexity-report defines maintainability as a function of not just cyclomatic complexity but also lines of code and overall volume of operators & operands (effort):

Suffice it to say, it gives more accurate picture of code simplicity and maintainability.

Vanilla JS

It all started with this one big, linear, 1057 LOC JS file. Kitchensink never had any complex DOM/AJAX interactions or animations, so I never even used jQuery in there. Just a plain vanilla JS.

Introducing jQuery

I started by porting all existing DOM interactions to jQuery. I wasn’t expecting any great improvements in code; jQuery can’t help with architectural changes. But it did remove some repetitive code - class handling, element removal, event handling, etc.

It would have also provided good foundation for further improvements, in case I decided to go with Backbone or any other higher-level tools.

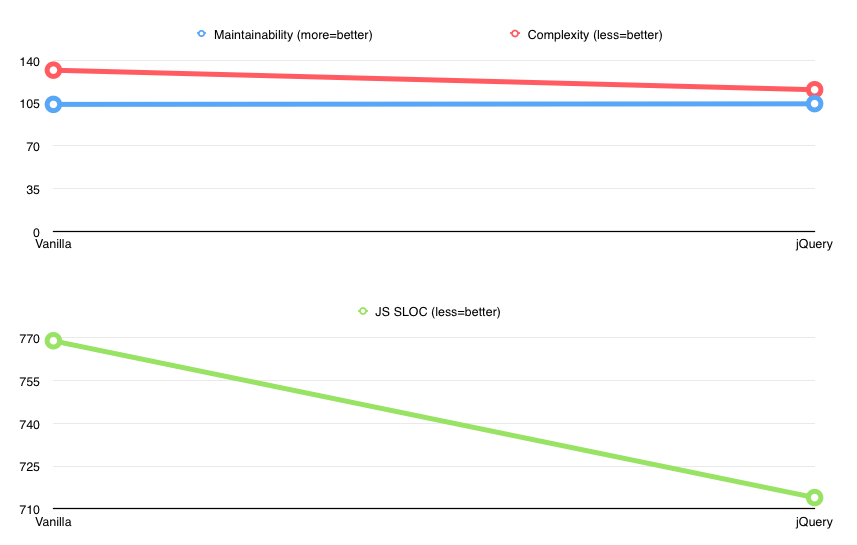

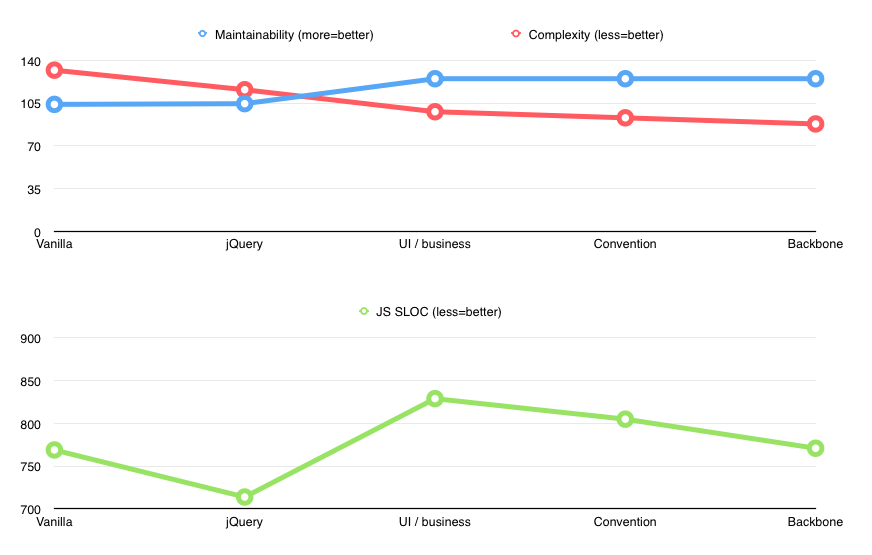

Notice how it shaved off ~50 lines of code and even improved complexity from 132 to 116 (mainly removing some DOM handling conditions: think toggleClass, etc.).

Backbone? Angular? Ember?

With easy stuff out of the way, I tried to figure out what to do next. I’ve used Backbone in the past, and I’ve been meaning to try out Angular and/or Ember — 2 of the most popular higher-level solutions. This would be a perfect way to learn them.

Still unsure of how to proceed, I decided to do something very simple. Instead of figuring out which library is the be-all-end-all, I went on to fix the most obvious issue — tight coupling of view logic and all the other (let’s call it “business”) logic.

Separating presentation and “business” logic

I broke kitchensink.js into 3 files: model.js, view.js, and utils.js.

Utils were just some language-level methods used by the app (like getRandomColor or supportsColorpicker). View was to contain purely UI code, and it would reach out to model.js for any state or actions on that state. I called it model.js but really it was a combination of model and controller. The bottom line was that it had nothing to do with the presentation logic.

So this kind of mess (in previous code):

was now separated into view concern:

and model/controller concern:

Separating presentation logic from everything else had a dramatic effect on the state of the app.

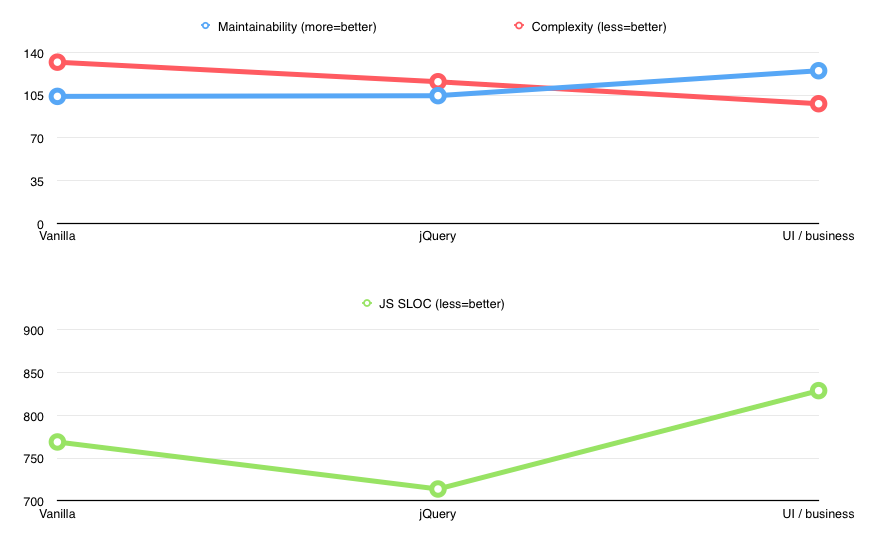

Yes, there was an inevitable increase in lines of code (714 -> 829) but both complexity and maintainability skyrocketed. Overall CC went from 116 to 98, but more importantly, it was significantly less per-file. The biggest chunk was now in the model (cc=70) and the view became thin and easy to follow (cc=26).

Maintainability rose from 104 to ~125.

Introducing convention

Looking at the code revealed few more possible optimizations. One of them was to use convention when enabling/disabling buttons representing canvas object actions. Instead of keeping references to them in the code, then disabling/enabling them through those references, I gave them all specific class name (“btn-object-action”) right in the markup, then toggled their state with the help of jQuery.

The changes weren’t very impressive, but complexity of the view went down from 26 to 21, SLOC went from 829 to 805. Not bad.

Backbone

At this point, the app complexity was concentrated in model/controller file. There wasn’t much I could do about it since it was all pure “business” logic: creating objects, manipulating objects, keeping their state, etc.

However, there was still some room for improvement in the view corner.

I decided to start with Backbone. I only needed a fraction of its capabilities, but Backbone is relatively “lean” and provides a nice, declarative abstraction of certain common view operations, such as event handling. Changing plain kitchensink view object to Backbone.View would allow to take advantage of that.

Instead of assigning event handlers manually, there was now this:

First application of (Backbone-esque) MVC

At the same time, model-controller was now implemented as Backbone.Model and was letting views know when to update themselves. This was an important change towards a different architecture. View was now observing model-controller for changes, and re-rendering itself accordingly. And model-controller fired change event whenever something would change on canvas itself.

In model-controller:

Remember I mentioned abstract canvas state and interactions?

Notice the bridge between canvas and model/controller object: “object:selected”, “object:added”, “selection:cleared” canvas/Fabric events were all forwarded as controller’s “change” one.

In view:

As an example, now when user selected an object canvas, model-controller would trigger change event and view would re-render itself. Then during render, view would ask model-controller — is there active object? — and depending on an answer, render corresponding buttons in either enabled or disabled state, with one text or the other.

This felt like a good improvement in the right direction, architecture-wise.

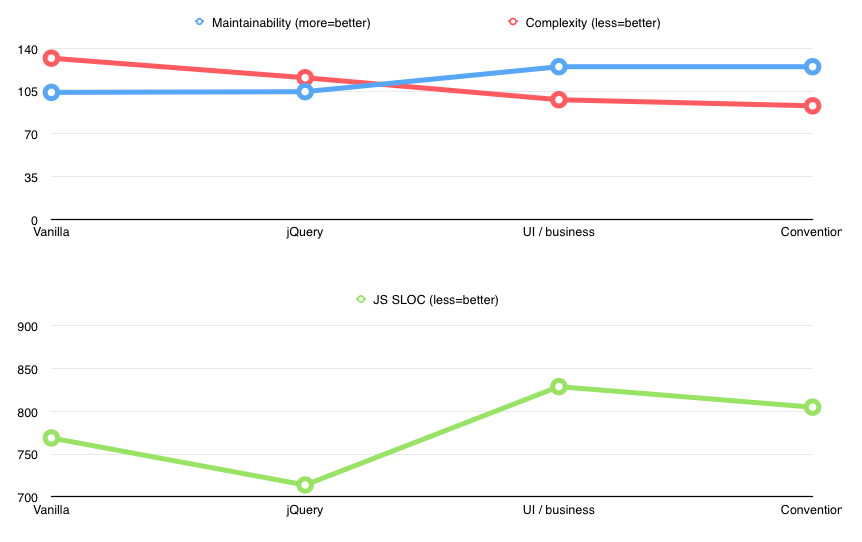

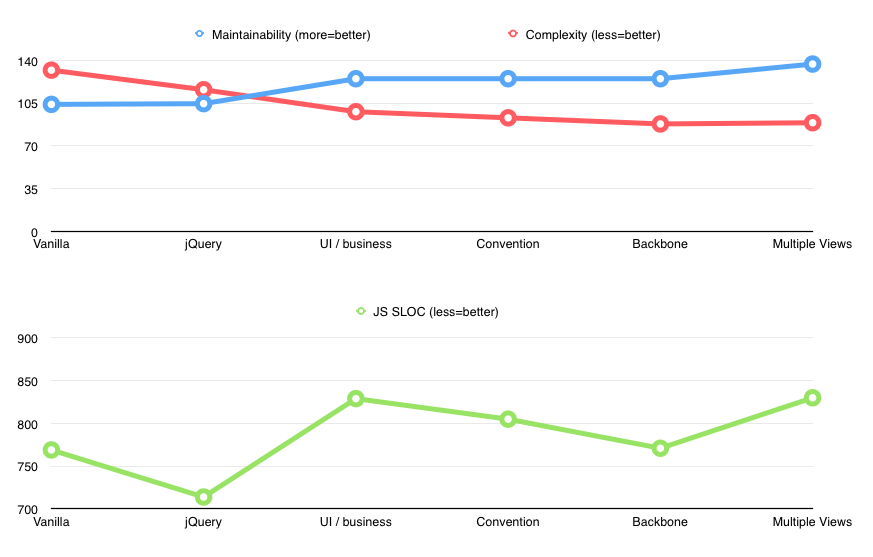

Views became more declarative and easier to follow. SLOC went down a bit (787 -> 772), and view complexity was now even less (from 21 to 16). Unfortunately, maintainability of model went slightly down.

Backbone.unclassified

Backbone made views more declarative, but there was still some repetition I wasn’t happy with:

Notice how “#lock-horizontally” selector is repeated twice. This is bad both for maintainance (my main concern) and performance. In the past, I’ve used a tiny backbone.unclassified extension to alleviate this problem, and so I went with it again:

Notice how we create an “identifier” for an element in ui “map”, and then use that identifier in both events “map” and in the rendering code.

This made views even more declarative, albeit at the expense of slightly more cruft overall. Complexity and maintainability stayed more or less the same.

Breaking up the view

The KitchensinkView was already clean and beautiful. Half of it was simple declarative one-liners (clicked this button? call that model method) and the rest was pretty simple and linear rendering logic.

But there was something else.

Entire view logic/rendering of an app was stuffed in one file. The declarative “events” hash, for example, was spanning ~200 lines and was becoming daunting to look through. More importantly, this one file included multiple concerns: object controls section, section for adding objects, global canvas controls section, text handling section, and so on. Yes, these are all view concerns but they’re also logically distinct view concerns.

What to do? Break it into multiple views!

The code size obviously increased once again, but look what happened with views maintainability. It went from 132 to 145! A significant and expected improvement.

Of course I didn’t need complexity report to tell me that things got better. I was now looking at 5 beautiful concise view files, each with its own rendering logic and behavior. As a nice side effect, some of the views (e.g. AddCommandsView) became entirely declarative.

2-way binding

At this point, I was fully satisfied with the way things turned out.

Backbone (with unclassified extension) and multiple views made for a pretty clean app. Backbone felt almost perfect here as there was none of the more complicated logic of nested views/collections, animations/transition, routing, etc. I knew that adding new functionality or changing existing one would be straightforward; multiple views meant easy scaling and easy addition of new ones.

What could possible be better…

Determined to continue further and see where it takes me, I took another look at the views:

This is ObjectControlsView and I’m only showing 2 functionalities here: lock toggling button and opacity slider. Notice how both of their behavior have something in common. There’s event (“click” or “change”) that maps to a model action, and then there’s rendering logic — updating button text or updating slider value.

Don’t you find the cruft inside render just a bit too repetitive and unnecessary? Wouldn’t it be great if we could just update “opacity” or toggle lock value on a model, not caring about rendering of corresponding control? So that opacity slider automatically knew to update itself, once opacity on a model changed. Ditto for toggling button.

Did someone say… data binding?

Of course! I just had to see what introducing data-binding would do to an app. Unfortunately, Backbone doesn’t have it built-in, unlike other MV* solutions — Knockout, Angular, Ember, etc.

I wanted to stick to Backbone for now, instead of trying something completely different, which meant using an addon of some sort.

backbone.stickit

I tried backbone.stickit first, but couldn’t get it to work at all with kitchensink’s model/controller methods.

You see, binding view to a regular Backbone model is easy with “stickit”. Just define a hash with selector ↔ attribute mapping:

Unfortunately, our model is <canvas>-based and all the state needs to be set & retrieved via a proxy. This means using methods, not properties.

We can’t just map opacity slider to “opacity” attribute on a model. We need to map it to canvas.getActiveObject().opacity (possibly checking that getActiveObject() returns object in the first place) via custom getters/setters.

Epoxy

Next there was Epoxy.js, which defines bindings like so:

Again, easy with plain attributes. Not so much with methods. I tried to implement it via computed properties but without much success.

Rivets.js

Next there was Rivets.js and as I was expecting another painful “adaptation”, it surprisingly just worked outside of the box!

Rivets turned out to be pretty low-level, but also very flexible. Docs quickly revealed how to use methods instead of properties. The binding could be initialized like so:

And the markup would then be parsed for any “rv-…” attributes (prefix could be changed). For example:

The great thing was that I could just write app.getBgColor and it would call that method on kitchensink since that’s what was passed to rivets.bind() as an app. No limitations of only working with Backbone.Model attributes. While this worked for one-way binding, with 2-way binding (where view also needs to update the model), I would need to write custom adapter…

It sounded daunting but turned out rather straighforward:

Now, I could add this in markup (notice the use of special ^ separator, instead of default .):

..and it would use a nice convention of calling getCanvasBgColor as a getter and setCanvasBgColor as a setter, when changing the colorpicker value.

There was no longer a need for manual (even if declarative) event listeners:

Downsides of markup-based bindings

I didn’t exactly like this whole setup.

I’d prefer to have bindings right in the code, to have a “birds-view” understanding of which elements map to which behavior. It would also be easier and more understandable to map multiple elements. If I wanted a set of buttons to toggle their enabled/disabled state according to certain state of canvas — and I did want that — I couldn’t just do something like:

I had to write custom binder instead, and that’s certainly more obscure and harder to understand. Speaking of custom binders…

Rivets makes it easy to create them. Binders are those “rv-…” directives we saw earlier. There’s few built-in ones — “rv-value”, “rv-checked”, “rv-on-click” — and it’s easy to define your own.

In order to toggle buttons state, I wrote this simple 1-way binder:

It was now possible to use “rv-enable” on a parent element to enable or disable descendant buttons:

But imagine reading unknown markup like this, trying to understand which directive controls what, and how far it spans…

Another binder I added was “rv-val”, as an alternative to “rv-value” (with the exception of observing “keyup” rather than “change” event on an element):

You can see that adding binders is simple, they’re easy to read, and you can even reuse existing behavior (rivets.binders.value.routine in this case).

Finally, there’s a convenient support for formatting, which was just perfect for changing toggleable text on some elements:

Notice how “rv-text” contents include | toggle smth smth. This is a custom formatter, defined like this:

The button text was now determined according to app^horizontalLock (which desugars to app.getHorizontalLock()) and when passed to toggle formatter, would come out either as one or the other. Unfortunately, formatter falls a bit short; it seems that its values can’t be strings, which makes things much less convenient.

Unlike with behavior, keeping alternative UI text directly in HTML felt perfect. Text stays where text should be — in markup; it makes localization easier; it’s easy to follow.

On the other hand, I didn’t like keeping model/controller actions right in the markup:

It’s especially bad when some of the view behavior is somewhere in a JS-based view/controller, and some — in the markup. YMMV.

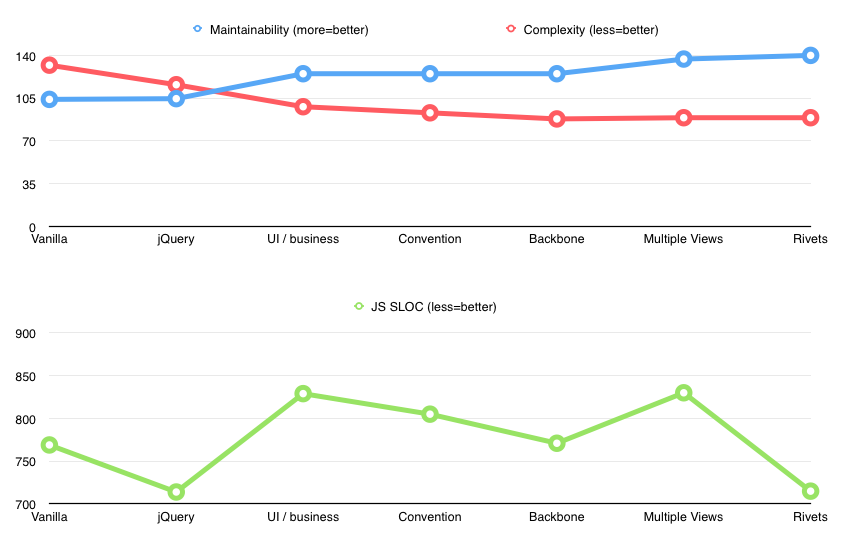

So what happened to the code?

After moving app logic from JS views to HTML (via Rivets’ “rv-“ attributes), all that was left from the views were these 3 lines:

Amazing, right? Or not so much?

Yes, we practically eliminated JS-based view, moving logic/behavior to markup and/or model-controller. But let’s look at the stats:

There was now additional (32 SLOC) data_binding_adapter.js file which included all the customizations and additions for Rivets.js. Still, there was a dramatic reduction of SLOC (830 -> 715); expected, since a lot of logic was moved to the markup. View’s maintainability was still ~145 but model-controller surprisingly went from 116 to 125! Even though more code moved to model-controller, that code was now simpler — usually a pair of getter/setter’s for particular state.

So how does this compare to the very first step — a monolythic spaghetti code?

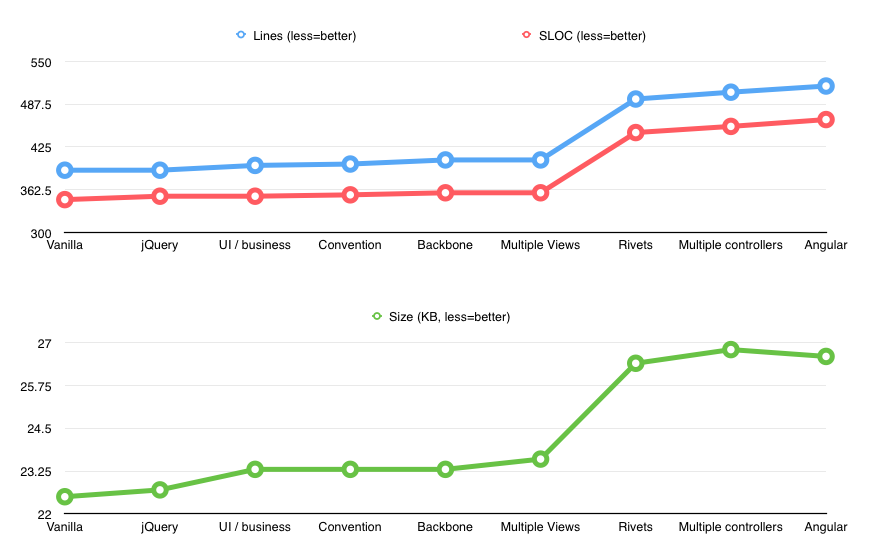

Improvement across the board. And what about HTML, where so much logic was moved to?

Ok, 100 lines longer, and only 3KB heavier. Doesn’t seem too bad.

But was this really an improvement? All the HTML declarations and all the abstraction felt like 1 step forward, 2 steps back. It seemed harder to understand and likely harder to maintain. While complexity tool showed improvement, it was only improvement on JS side, and of course it couldn’t give holistic analysis.

I wanted to take a step back and try something else.

Breaking up controller

Aside from markup contamination, the problem was model-controller becoming too fat; that one file that was still sitting at 70 complexity.

What if I could keep Rivets.js for now, but break model-controller into multiple controllers, each for distinct behavior. And a very thin model would serve as a proxy between <canvas> and controller actions. After some experimentation and pondering on a best way to organize something like that, I ended up with this:

The model was now <canvas> itself! There were no JS-based views, and all the logic was in 5 distinct controllers. But how was this possible? Shouldn’t canvas actions go through some kind of proxy to normalize all the canvas.getActiveObject().{get|set}Something() voodoo? Yes, it was still needed, but all the proxying was now happening in controller itself.

I created CanvasController, inheriting from Backbone.Model (to have event managing), and gave it very minimal generic behavior (getStyle, setStyle, triggerChange). Those methods are what served as proxy between canvas and controllers. Controllers implemented specific getters/setters via those methods (inherited from a parent CanvasController “class”).

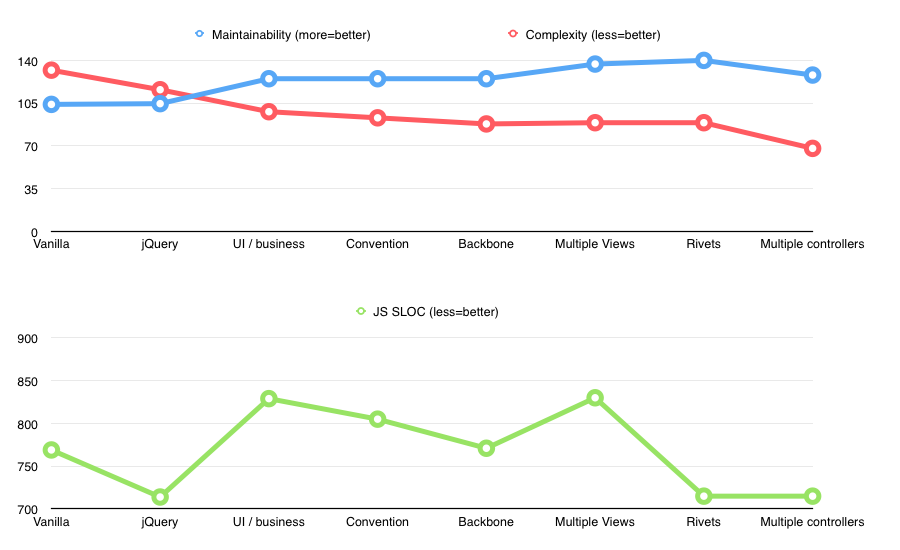

How did this all look complexity-wise?

SLOC stayed the same but what happened to complexity? Not only it went down to total of 68, the max complexity per file was now only 18! There was no longer a big business logic file cc=70, but small controller files with cc<=20. Definitely an improvement.

Unfortunately, maintainability went slightly down (to 128), likely due to all the additional cruft.

Even though this was the best case complexity-wise, I still wasn’t too happy with this solution. There were still bindings in HTML and canvas controllers felt a bit too overly abstracted (i.e. it would take some time to understand how app works, how to change or extend it).

Angular

Muliple controllers reminded me of what I’ve seen in Angular tutorials. It seemed natural to try and see how Angular compares to the last (Backbone + Rivets) solution, since it looked so similar.

Angular learning curve is definitely steeper. It took me ~2 days to understand and get comfortable with Rivets data-binding. It took ~2 weeks to understand and get comfortable with Angular data-binding (watches, digest cycle, directives, etc.).

Overall, implementing kitchensink via Angular felt very similar to Backbone + Rivets combo. But, as with everything, there were pros and cons.

The Good

In Angular, there’s no need to Function#bind methods to a model (when calling them from within attribute values). For example, rv-on-click="app.foo" calls app.foo() in context of element, whereas Angular’s ng-click="foo()" calls foo in context of $scope. This proves to be more convenient.

Using the same example of rv-on-click="app.foo" vs. ng-click="foo()", braces after name make it more clear that it’s a function call.

Function calls are also more concise. For example, rv-show="app.getSelected" vs. ng-show="getSelected()". There’s no need to specify app since getSelected is looked up automatically on $scope.

Mostly syntactic preference, but

<button>{{ ... }}</button> (in Angular) is easier to read/understand than <button rv-text></button>.

The not so Good

The biggest drawback was getting started and understanding how to plug kithchensink’s unique “model” into Angular. I was also unlucky to have run into an issue with {{ … }} conflicting with Jekyll’s {{ … }}. Took quite some time to figure out why in the world Angular was not “initializing”…

It’s a bit annoying that Angular’s methods start with $ and “interfere” with a common convention of referencing jQuery objects via $xxx. Just a minor additional cognitive burden if you’re used to that notation.

There were some minor things like Angular’s $element.find() limiting lookup by tagName even when jQuery was available. Weird.

Most importantly, custom 2-way binding was non-trivial, unlike with Rivets documentation which made it very clear. With Angular, it’s pretty much impossible to use custom accessors in attribute values. We can’t do that elegant Rivets trick of app^selected desugaring to app.getSelected() and app.setSelected(). Of course Angular’s directives kind of solve this, but it’s not the same.

Why? Because in Rivets, you can plug this custom adapter anywhere, including Rivet’s “native” binders!

Take this radio group, use built-in rv-checked attribute, and it just works:

This can not be done in Angular, and so we need to implement our own “radio group” handling via directive. Directives are somewhat similar to Rivets’ ones, although of course much more powerful.

To implement accessors, I created bindValueTo directive, to be used like this:

Now, slider would call getFontSize() to retrive the value, and setFontSize(value) to set it. Once I understood directives, it was fairly straightforward:

Notice the additional $element[0].type === 'radio' branch for that radio group case I mentioned earlier.

Clarity vs. Abstraction

When it comes to Angular, I feel it’s important to strike a balance between abstraction & clarity. Take this toggle button, for example. A common chunk of functionality in kitchensink, used a dozen times.

Now, this is a fairly understandable piece of markup — putting the issue of mixed content/behavior aside — accessor methods toggling the state, element class and text updating accordingly. Yet, this is a common functionality. So to avoid repetition, it could be abstracted away into its own directive.

Imagine it being written like this:

Certainly cleaner and easier to read, but is it easier to understand? As with any abstraction, there’s now an extra level underneath, so it’s not immediately clear what’s going on.

So how did porting to Angular affect complexity/maintainability scores?

Comparing to previous Backbone/Rivets combo, SLOC went from 715 to 660. Complexity — from 68 to 65, and maintainability — from 128 to 126. Interesting.

The reduction in SLOC was expected, knowing Angular’s nature of controller “entrees” right in markup. Complexity and maintainability, on the other hand, practically stayed the same.

HTML size

If you’re wondering how this refactoring affected size of the main HTML file, the picture is very simple and straightforward.

As expected, it’s been continuously growing little by little, with the spike from markup-based solutions like Rivets and Angular. Curiously, while Angular resulted in higher SLOC, it was actually less KB comparing to Rivets.

To summarize

Unfortunately, other MV* libraries (Ember, Knockout, etc.) didn’t make it into my exploration. I was constrained on time, and I’ve already came to a much more maintainable solution. I do hope to try something else in the near future. It’ll be interesting to see how yet another concept ties into the app. Stay tuned for part 2.

My final conclusion was that Backbone+Rivets and Angular provided relatively similar benefits, with almost exact complexity/maintainability scores, and only different distribution of logic (attributes in markup vs. methods in JS “controller”). The pros/cons I mentioned earlier are what constituted the main difference.

TLDR and Takeaway points

-

Path of exploration: Vanilla JS (initial mess) -> jQuery (cleaner) -> UI/business logic separation (much cleaner) -> Backbone (slightly better) -> Backbone.unclassified (slightly better) -> Backbone & multiple views (significantly better) -> Rivets (better or worse?) -> Multiple controllers (possibly better) -> Angular.js (better or same?)

-

MVC framework is not always necessary when refactoring or creating small/medium-sized client-side app. Separating presentation logic from “business” logic is often enough to produce clean and maintainable architecture.

-

Backbone is great but almost always comes out a bit too low-level. Backbone.unclassified is a great addition to remove some repetition in the views.

-

Rivets.js is a nice library-agnostic data-binding tool, that could be used on top of Backbone to remove lots of repetitive view logic.

-

Complexity tools like

complexity-reportorJSHintcan aid with refactoring but shouldn’t be followed blindly. Use common sense and time-tested principles (SRP, DRY, separate presentation logic) when refactoring/designing an app. -

Don’t forget to look at a big picture. When the size of JS goes down, what happens to the markup? It could be that you’re just shifting things around without any significant improvements.

Did you like this? Donations are welcome

comments powered by Disqus